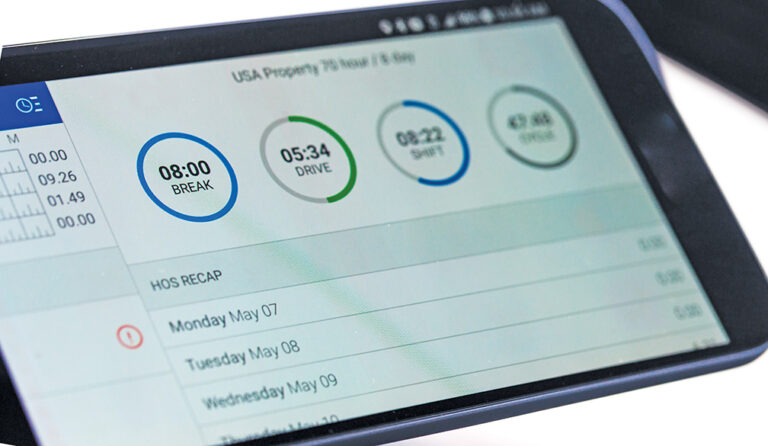

With the mandate for electronic logging devices (ELDs), the method of recording a driver’s hours of service (HOS) has changed a lot. However, the principles behind getting the most from those hours hasn’t changed at all. It’s still all about efficiency — spending the most available time doing what you are paid the most to do.

As a driver, recording your duty status can seem like an exercise in fighting the system.

Let’s start with the 14-hour rule. Under this rule, once you have accumulated 14 total hours of any combination of driving and on-duty time, you must stop driving until you have completed a 10-hour rest break. Sometimes a driver might describe it as “14 hours per day,” but that’s a figure of speech and is not really accurate; the 14-hour period can fall across different days.

Note that there is no requirement to stop working. You can work around the clock if you like — as long as you don’t get behind the wheel until you’ve had 10 hours of rest. That 10 hours can be logged as sleeper berth time or as off-duty time. There is no obligation to spend any certain number of hours in the sleeper berth, unless….

If you decide to split your sleeper berth time into two periods, one of them must be at least seven consecutive hours spent in the sleeper berth. The other three hours can be either “off duty” or in the sleeper. If you’re driving as a part of a team, there’s a limit to how much time you can log as “off-duty” while you’re in the passenger seat in a moving truck: At least eight hours of the 10-hour break must be spent in the sleeper. Of course, if the truck stops, so does the requirement for logging sleeper berth time.

There’s another rule that has a severe impact on the 14-hour rule, and that’s the 60/70 hours in 7/8 day rule. Whether you work for a carrier or drive for yourself, if the business operates seven days a week, your working and driving hours together can’t add up to more than 70 hours over an eight-day period.

Even though you’re allowed to work 14 hours a day, if you use all of those hours, your accumulated total will reach 70 hours after just five days. As with the 14-hour rule, you can work all you want, logging all the on-duty/not driving hours you can stand. But you can’t drive again until your hours for the eight-day period (think: today plus the past seven days) falls under 70.

The answer most drivers choose is a 34-hour restart. If you log 34 consecutive hours off-duty — sleeper berth or any combination — your hours total resets to zero.

The trick for most drivers and their dispatchers is spending that 34 hours somewhere the driver wants to be (such as home). Few drivers like killing off 34 hours stuck at a truck stop or a company terminal. If you know you’ll need a reset in the next day or two, try to find a load that’s heading towards home.

If you’re paid by the mile, the 11-hour driving rule directly equates to your paycheck. Unfortunately, the number of miles you can drive in that period is impacted by traffic congestion, accidents, weather and other factors that are mostly beyond your control.

In the “good old days,” drivers were able to take breaks during periods of heavy traffic, choosing to nap a couple of hours now and drive later, when traffic thinned out. Cruising down the interstate at 60 mph pays a lot better than averaging 20 mph in stop-and-go traffic.

With the 14-hour rule, the driver’s ability to manage hours was curtailed. That two-hour nap still counts as part of the 14-hour driving/working period, so the driver will have used up two hours of driving time (if the total driving/working time exceeded 14).

On June 1, 2020, the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration issued a final rule that allows the driver to split the 10-hour break into two periods without counting against the 14-hour clock. One of the periods must be at least seven hours long, and it must be in the sleeper berth. The other period must be at least two hours long, but it can be either off duty or sleeper berth time.

Split logging is easy for some drivers but confusing to others. Remember, the last TWO break period must add up to at least 10 hours, and the last TWO work/drive periods can’t add up to more than 14.

The rule that expanded split logging hours also changed two other rules. One is the requirement for a 30-minute rest break. You must take a half-hour break once you have driven eight consecutive hours. You can take the break any time you want; but if you then drive for eight hours, you’ll need another break.

The rule change allows you to use on-duty/not driving time for this requirement, so time spent fueling and inspecting your vehicle or performing other work can count.

Perhaps the most confusing of the rules is the adverse driving conditions requirement that gives you an additional two hours if you encounter severe conditions. Before the change, you could drive an extra two hours but the 14-hour work/drive period stayed the same. Now you can also extend the 14-hour period.

While the adverse driving conditions clause can be useful, be careful how you use it. You’ll need to be able to convince an inspector that the adverse conditions were legitimate. Citing an Oklahoma blizzard in mid-August might look suspicions, as might a claim of a huge traffic jam that the trooper has no knowledge of. Sure, you might be able to prove it in court, but do you really want the whole ticket and court routine?

Hours-of-service regulations can certainly be a drain on your ability to get the job done and get paid for doing it. With some common sense and a little management, however, you can take maximum advantage of the hours allowed. In a business where every mile counts, it’s important to rack up all you can, while you can.

Cliff Abbott is an experienced commercial vehicle driver and owner-operator who still holds a CDL in his home state of Alabama. In nearly 40 years in trucking, he’s been an instructor and trainer and has managed safety and recruiting operations for several carriers. Having never lost his love of the road, Cliff has written a book and hundreds of songs and has been writing for The Trucker for more than a decade.