The “Country Gold” era (early 1950s to mid-1970s) gave rise to a few real-life truck drivers who took shots at making their names in the music business, either in Nashville, Tennessee, or on the west coast in Bakersfield, California.

None rose higher than Elvis Presley, a performer who erased the boundaries of musical genres worldwide. In high school, “The King” drove a truck for an electric company — but he knew his future awaited him behind a microphone, not a steering wheel. He must have been a pretty good driver. After all, when Presley met with Eddie Bond, a Memphis band leader who was looking for a vocalist, Bond told him to stick to driving trucks. Shortly thereafter, Presley recorded “That’s Alright (Mama).” Eddie Bond ate the crow Presley left in the lunch pail in the seat of his electric-company truck.

Ferlin Husky was another truck-driver-turned-musician, first appearing on the charts about a decade before Presley. Born in 1925 in Cantwell, Missouri, Husky began a seven-decade career in St. Louis in the early 1940s. Over the years, he performed a variety of country music styles including honky-tonk, ballads, recited songs and even the occasional rockabilly tune. He never joined the early 1960s fray of artists performing truck-driving songs, but Husky did have a road song or two in him.

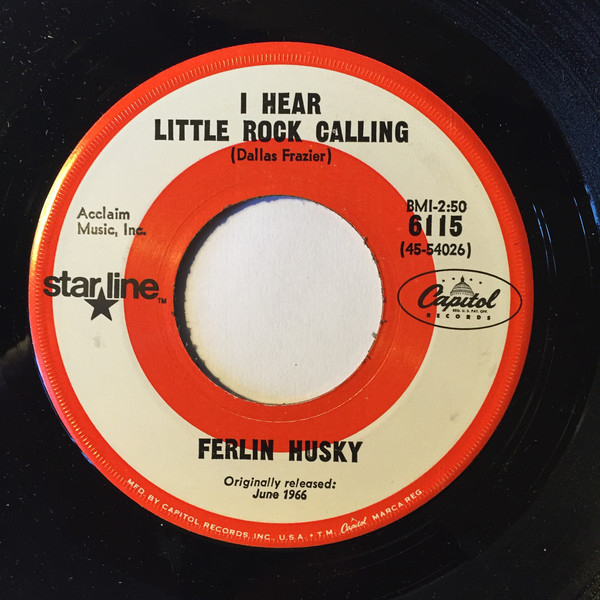

“I Hear Little Rock Calling,” a 1966 road song penned by Dallas Frazier, gave Husky a No. 17 hit. But in hindsight, with the change of a single word, Husky and Frazier might have recorded a trucker’s anthem to put all other anthems to shame. Fortunately, more than 50 years later, we have the hindsight the singer-songwriter combo lacked. Today, we can make the change, and we don’t even have to worry about infringing on a copyright.

Before Husky found stardom — or maybe before stardom found him — he paid his dues, working in a steel mill and as a truck driver while playing St. Louis honky-tonks at night. Then he served a stint in World War II as a merchant marine, entertaining soldiers who were headed to the battlefronts of Europe on transport ships, including at least one shipload filled with young men destined to invade Normandy on D-Day.

After the war, Husky took a job as a disc jockey, a job that gave him access to record executives and promoters. He recorded a few albums — but they weren’t under his given name. A record promoter decided the words “Ferlin Husky” wouldn’t be an appealing site on a venue’s marquee. Instead, he convinced Husky to adopt a stage name, “Terry Preston.” The name brought no success, and when Husky signed with Capitol Records in 1953, he drove Terry Preston and the promoter to a bus headed to music’s hall of shame. The two were last seen bordering the bus, right behind Elvis Presley’s detractor, Eddie Bond. It’s a fine line between fame and infamy.

Husky’s first two singles, both duets with Jean Shepard, screamed to the top of the charts. The first, “A Dear John Letter,” gave Husky a No. 1 record with his first single. The second single, “Forgive Me John,” hit No. 4. Over the next couple of years, Husky charted a few more songs, including the No. 1 “Gone” in 1957, a song that crossed over to the pop charts. But it wasn’t until 1960 that Husky achieved country superstar status with his signature hit “On the Wings of a Dove.” The song held the No. 1 spot on country charts for 10 weeks. Husky never recorded a bigger hit, and “On the Wings of a Dove,” is frequently noted as an all-time top country hit.

With notoriety on his side, Huskey had arrived. A popular performer on radio and stage, he made the transition to television, appearing with Ed Sullivan and Merv Griffin, and on at least three episodes of “Hee-Haw.”

In the middle of it all, he recorded “I Hear Little Rock Calling,” until now just one in a chain of road songs in the vein of Roger Miller’s “King of the Road” and Charley Pride’s “Is Anybody Going to San Antone?” While not as popular as many other road songs, Husky’s recording is pure country, flawlessly expressing the feelings of young men who lament leaving home before they are ready. In fact, the lonesome road and regret of ignoring his parents’ advice and pleas to remain at home are evident in Husky’s opening lines:

“I hear Little Rock calling, homesick tears a falling,

“I’ve been away from Little Rock way too long…

“…they said, Son, don’t go away. Now I wished I would’ve listened to their call….”

The song goes on to sum up life on the road in a few well-chosen words. Husky misses “Mom and Dad and the many good friends he had,” but he misses his “hometown sweetheart most of all.” Likewise, the lyrics reveal that the “thrill of traveling this old world is gone,” as well as the heart of the matter: “I’m troubled in my soul.” In the song, Husky decides to jump the next train home. As he heads toward Little Rock, excitement builds — after all, “I’m gonna have a worried mind ’til I cross that Arkansas line.” Little Rock continues to call.

So, exactly how did Frazier and Husky miss out on scoring a timeless trucker’s anthem? In a song with otherwise flawless lyrics, they chose just one word incorrectly: “train.” Had Husky jumped a “truck” instead of a “train,” he might have recorded a nearly perfect trucking song. And with highways filled with drivers substituting their own hometowns for “Little Rock,” truckers alone might have carried the song to legendary status. Then again, hindsight always serves us well.

Until next time, stay off those trains and just follow Ferlin Husky’s voice back home. Those tears will wash away with every passing mile.

Since retiring from a career as an outdoor recreation professional from the State of Arkansas, Kris Rutherford has worked as a freelance writer and, with his wife, owns and publishes a small Northeast Texas newspaper, The Roxton Progress. Kris has worked as a ghostwriter and editor and has authored seven books of his own. He became interested in the trucking industry as a child in the 1970s when his family traveled the interstates twice a year between their home in Maine and their native Texas. He has been a classic country music enthusiast since the age of nine when he developed a special interest in trucking songs.