By 1919, America’s troops had returned from World War I having experienced the first significant use of mechanized warfare.

During the war, trucks played a crucial role in military operations. The Liberty Truck was the first motor vehicle ever commissioned for wartime use, transporting troops, equipment and supplies. Ten thousand Liberty Trucks were manufactured.

The use of these trucks changed warfare, providing for a mobile army that could be repositioned faster than any army had ever been able to move before. This played a vital role in America’s success during the war.

Upon returning home, officials decided it was time Americans were introduced to what the nation’s “new” army could accomplish.

To this end, the U.S. Army Motor Transport Corps organized the Motor Transport Convoy and mapped out a route from Washington D.C. to San Francisco. The goal of the convoy? To demonstrate the benefits of mechanized travel.

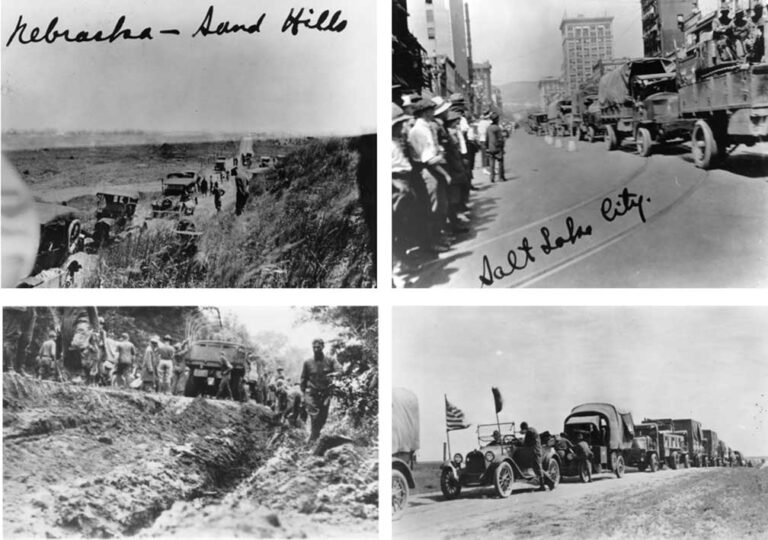

The 3,000-mile overland transport was to follow the famed Lincoln Highway, much of which is now known as Interstate 80. The convoy consisted of 81 vehicles, including 34 heavy cargo trucks and four light delivery vehicles, along with a host of specialized vehicles including ambulances, a wrecker, motorcycles and mobile machine shops. Manufacturers of the vehicles in this convoy included, among others, Cadillac, Dodge, Harley-Davidson, Indian, Mack and White.

According to the schedule, the convoy was to travel at 18 mph. At times, it reached up to 32 mph. However, on average, the fleet managed to travel only at 5.65 mph — the convoy was slowed by delays and breakdowns, especially early in the trip.

The Army Motor Transport Corps attributed many of these delays to inexperience among operators and mechanics whom Lt. Colonel Dwight D. Eisenhower or the Army Tanks Corps described as “raw and undisciplined.”

The convoy set out on its travels with four primary goals:

- To encourage construction of through routes and transcontinental highways.

- To procure recruits for the Motor Transport Corps.

- To exhibit the military motor vehicles at the nation’s disposal.

- To observe the terrain and standard army vehicles’ performance.

The roadways the convoy encountered were varied and ranked in condition from very good (though narrow) concrete roads to roadways of dirt and sand. Eisenhower’s notes about the convoy’s progress provide insight into the successes and challenges it faced as it crossed the country.

For instance, he noted that in states that had good highways, the heavy-duty vehicles could not keep up with the lighter vehicles, observing that “in general, the two types should not be mixed for transport work.” The heavier vehicles also performed poorly in sand and on steep grades. In many cases, they had to be pulled through these stretches while the lighter vehicles passed with ease.

The result was a trip that remained reasonably on schedule from Washington D.C. to Illinois before encountering problems as the convoy pushed westward. Dust became a major issue, creating problems for motorcycles and larger vehicles alike.

In regard to the road conditions, Eisenhower noted:

“Through Ohio and Indiana a great portion was paved and macadamized. In Illinois train started on dirt roads, and practically no more pavement was encountered until reaching California.

The dirt roads of Iowa are well graded and are good in dry weather; but would be impossible in wet weather. In Nebraska, the first real sand was encountered, and two days were lost in western part of this state due to bad, sandy, roads. Wyoming roads west of Cheyenne are poor dirt ones, broken through by the train. The desert roads in the southwest portion of this state are very poor.”

Eisenhower went on to state that the Salt Lake Desert of Utah was virtually impassable, and in Nevada the roads were a “succession of dust, ruts, pits and holes.” He described the roads in this area as unimproved, consisting of only “a track across the desert.”

Based on these observations, it can be assumed Eisenhower believed that consideration of the Lincoln Highway’s placement as a transcontinental route should be closely studied.

As general observations, Eisenhower noted:

“The truck train was well received at all points along the route. It seemed that there was a great deal of sentiment for the improving of highways, and, from the standpoint of promoting this sentiment, the trip was an undoubted success.”

Reports indicated that more 3 million Americans watched the convoy as it moved along its route which passed through 350 communities.

Eisenhower went on to report that the Motor Transport Corps “should pay more attention to disciplinary drills for officers and men, and that all should be intelligent, snappy soldiers before giving them the responsibility of operating trucks.”

Likewise, he stated that “extended trips by trucks through the middle western part of the United States are impracticable until roads are improved, and then only a light truck should be used on long hauls.”

He concluded his report with the observation that “through the eastern part of the United States the truck can be efficiently used in the Military Service, especially in problems invoking a haul of approximately a hundred miles, which could be negotiated by light trucks in one day.”

Despite delays due to mechanical failures, breakdowns, road conditions, dust and an inexperienced convoy crew, the 1919 Motor Corps Convoy went down as a success in the early automotive history of America. While the convoy failed in its effort to recruit as many future members of the Motor Corps as it had hoped, its other three goals were successful, at least to a degree. The idea of transcontinental roadways was placed in the public conscious, and the effectiveness of such roadways opening up the nation to travel for commercial and military purposes was exhibited.

As far as Dwight D. Eisenhower was concerned, the convoy planted a seed in his mind of the future of American travel. Some 30-40 years later, his experience with the convoy would guide him in leading one of the most difficult public works projects in the nation’s history – the development of the Interstate Highway system.

Tune in next month for Part 2 of the convoy’s history and impact on travel and freight in the United States.

Since retiring from a career as an outdoor recreation professional from the State of Arkansas, Kris Rutherford has worked as a freelance writer and, with his wife, owns and publishes a small Northeast Texas newspaper, The Roxton Progress. Kris has worked as a ghostwriter and editor and has authored seven books of his own. He became interested in the trucking industry as a child in the 1970s when his family traveled the interstates twice a year between their home in Maine and their native Texas. He has been a classic country music enthusiast since the age of nine when he developed a special interest in trucking songs.

3 Comments