East and Gulf Coast ports shut down at midnight Oct. 1, 2024, as 45,000 union longshoremen walked off their jobs.

Freight will quickly back up as many parts of the Southeast work to recover from the devastation of Hurricane Helene, which hit the Big Bend area of Florida on Sept. 26 and wove a path of destruction reaching far beyond the coastline.

With the port strike, analysts expect the impact on import and exports to be $5 billion per day.

Coincidentally, exactly 86 years ago in New York City, a truckers’ strike affected shipping up and down the East Coast — when the area was hit by a Category 3 hurricane.

Here’s how the story goes.

By the late 1930s, trucking held a firm grip on commerce throughout the U.S. While railroads and seaports served cities on both coasts, it was trucks that delivered the bulk of the goods throughout the country and into cities, shuttling goods between terminals and delivering to stores and worksites.

While railroad workers had worked eight-hour days for many years, truckers weren’t provided the same working conditions.

The Motor Carrier Act proposed in 1937 would have allowed truckers to work up to 60 hours a week, with 12 hours a day behind the wheel. Even in large metropolitan areas like New York City, those extremes had not been considered; however, local trucking firms did require drivers to work 47-hour weeks at a pay rate of $56.50 per week.

The terms didn’t sit well with truck drivers.

When the drivers’ contracts expired on Sept. 1, 1938, employers pushed for truck drivers to take a pay cut. The drivers responded negatively, pushing for a new contract that would lower their work hours to 40 per week — with no pay cut and including one week’s vacation.

A large part of the motivation of the drivers’ terms were to spread work to the some 4,000 unemployed drivers in New York City. As Sept. 15 approached, the employers backed away from the 47-hour work week. Instead, they suggested a 44-hour week with no pay reduction.

Members of the truckers’ unions rejected the proposal, and 1,000 members went so far as to unofficially vote for a strike. On Sept. 15, Local 807 voted for an unsanctioned, or “outlaw” strike, across New York City. It was their belief that negotiators were not working to achieve the lower hours the union members wanted.

As the idea of a truckers’ strike began to gain steam, a hurricane was barreling up the East Coast. In a few days, there would be a need for relief efforts, and truck drivers would be a major contributor to relief to areas all along the Atlantic coast.

With an eye on the storm, another 1,000 workers voted to strike and 5,000 more were expected to follow. However, the truckers planned to honor their civic duty and agreed to deliver relief supplies as required.

Employers proposed five- and three-day truces to the growing movement toward a drivers’ strike.

The drivers involved rejected both.

Their position was strengthened when the Sailors Union of the Pacific agreed not to cross picket lines — and picketing of the Holland Tunnel between New York and New Jersey virtually brought interstate trucking to a halt. Eventually, this block on interstate trucking would impact over 2,000 gas stations in New York City.

By Sept. 20, over 12,000 striking truckers were in the city, 5,000 of them operating “driving picket lines” to enforce the strike effort. The next day, as acting mayor Newbold Morris ordered the strike to end in 24 hours, Long Island was struck by a Category 3 hurricane.

To date, the strike had interrupted deliveries for the 1939 World’s Fair construction and caused shipping lines along the East Coast to stop working the piers, as no freight was being moved. Similar stoppages happened along the Pennsylvania and New York Central railroad lines where freight piled up in warehouses.

With relief for those impacted by the hurricane taking priority, the union agreed to a temporary truce, which would last until Sept. 24.

Over the ensuing 48 hours, negotiators made no progress toward an agreement between the employers and drivers’ unions. A “real strike” was now a looming possibility.

Employers used the truce period to build a backlog of supplies in case a strike occurred, but road damage from the hurricane disrupted these efforts.

Then, when no agreement was reached at the end of the truce period, an official strike vote was held on Sept. 25, with 4,071 in favor of the strike and only 365 against.

The “real strike” was on.

Just one day later, 20,000 Teamsters union drivers in New Jersey voted to join their neighbors’ effort and fight for better working conditions.

Dealing another blow to the employers was the Longshoreman’s Union public statement that it would not attempt to disrupt the drivers’ strike. In addition, they announced that when their contract ended in just a few months they too would be asking for a 40-hour workweek.

During the official strike, truck drivers agreed to exempt food, medicine and relief goods from the strike embargo so vital supplies could be delivered to hurricane-stricken areas. Regardless, those enforcing the strike effort caught many drivers attempting to circumvent the rules and make ordinary deliveries under the premise of emergency relief efforts, placing “flood signs” on the windshields of their trucks.

New York City’s Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia spent a majority of the strike period out of the city. Upon his return, he found between 30,000 and 35,000 drivers on strike. He proposed new terms to both the strikers and employers.

First, LaGuardia suggested a two-year contract calling for a 44-hour workweek with no pay cut. This compromise would require drivers to work eight hours on weekdays and four hours on Saturdays — and the weekend work would be paid at time and a half.

All work over eight hours in a single day would be subject to the same overtime pay. However, drivers could not work more than 44 hours a week, regardless of overtime incurred Monday-Friday. In other words, if a driver worked a total of four hours of overtime during the regular workweek, the driver would not be allowed to work on Saturday.

The striking drivers voted to accept the terms; however, their employers initially resisted. Eventually, cracks formed in the employers’ opposition, and over the next several days, more drivers and employers broke ranks and agreed to LaGuardia’s terms.

The drivers’ strike ended on Oct. 2, 1938, when all major trucking firms agreed to the conditions.

The aftermath of the New York City truckers’ strike created some changes at the federal level.

No longer did the Motor Carrier Association push for a 60-hour workweek. To help ensure drivers were paid for their work, it initiated the use of driving logs. The agency also approved the use of “sleeper” cabs to address long-distance drivers and the need for rest periods along their routes.

Perhaps most importantly, the truckers’ strike made Americans recognize how important trucking had become to an economy that 20 years earlier was driven by railroad and wagons transporting freight.

That historic strike of 1938 also helped set the stage for interstate regulations related to trucking — and an increased the federal government’s involvement in the freight industry.

As port workers from Maine to Texas form picket lines in an attempt to better their working conditions, the question is this: The longshoremen supported truckers back in 1938. Will the trucking industry provide the same support back now?

Time will tell.

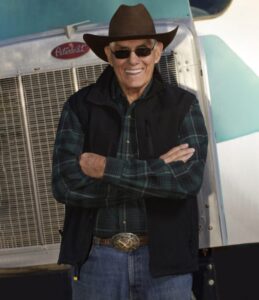

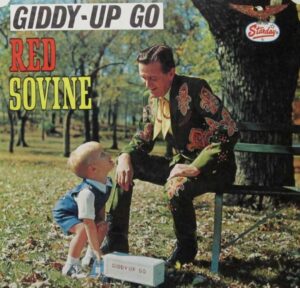

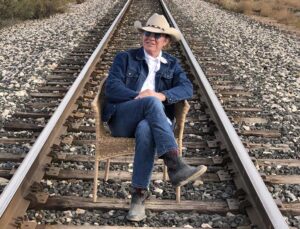

Since retiring from a career as an outdoor recreation professional from the State of Arkansas, Kris Rutherford has worked as a freelance writer and, with his wife, owns and publishes a small Northeast Texas newspaper, The Roxton Progress. Kris has worked as a ghostwriter and editor and has authored seven books of his own. He became interested in the trucking industry as a child in the 1970s when his family traveled the interstates twice a year between their home in Maine and their native Texas. He has been a classic country music enthusiast since the age of nine when he developed a special interest in trucking songs.

I don’t understand how they are able to strike with a National Emergency going on. I worked for the government. I could not say I’m on strike when Katrina happened. I worked on Katrina for 3 years. I was on call all the time. I got what they’re saying but there is no reason they should be doing it in this National emergency. I think it’s just disgusting.